Sabah’s newly named state butterfly is threatened by a double whammy

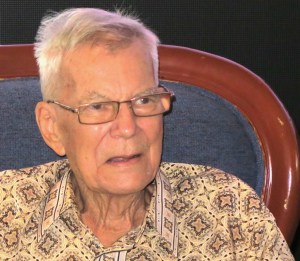

Despite its discovery 131 years ago, little is known of the rare and mysterious Kinabalu or Borneo Birdwing butterfly (Troides Andromache) which is struggling for survival. Its population is not known. But there may be about 5,000 of them left in the foothills of Mount Kinabalu, Malaysia’s tallest at 4,095 metres, according to Stephen Sutton, 85, a British entomologist. He has been at the fore front of the butterfly research project supported by the Kota Kinabalu Rotary Club that started six years ago and culminated in the Sabah government naming the giant birdwing its state butterfly on October 2. It is a belated attempt to save it from extinction. Wildlife officials say many of them have been wiped out by deforestation. But the butterfly now faces a new threat – climate change.

The wings of the Kinabalu Birdwing, endemic to Sabah, can span up to 20cm, the size of a small dinner plate. Strangely it is the only one known to thrive in the highland forests where harsh temperate climate prevails. Butterflies generally prefer warmer climes with plenty of sunshine. The Kinabalu birdwing, with yellow, white and black wings, however finds its home in the cold, windy and rainy forests of Kampung Kiau Nuluh, between 1,000 and 2,000 metres above sea level. This may be its last remaining habitat.

Nobody knows why the Kinabalu Birdwing, known officially as Kalibambang Emas (Golden butterfly) in the native Kadazandusun language, prefers the mountainous forests. Scientists postulate that stronger adversaries might have driven it to higher grounds. Dr Sutton says eventually there may be “nowhere to go” for the birdwing as there are few places higher than 2,000 metres. The new environment may be hostile to it. And it may not find suitable food. Little is known of the butterfly’s ecology and thus there have been no significant measures to protect it since the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) listed it as endangered in 1987.

In 2019, Dr Sutton with a handful of volunteers of the Rotary Club turned to eco-tourism to help conserve the birdwing. The idea was to get villagers who run homestays to lure tourists to Kiau to see the butterflies. But they are not easily seen. Dr Sutton says on a good sunny morning there might be ten or 20 of them fluttering around the vines. Tourists may have to spend three days at Kiau to get a glimpse of them. And they must be prepared to be disappointed when the butterflies don’t show up.

However there is room for optimism. Various species of birdwing larvae have been found feeding on a vine belonging to the Dutchman’s pipe family known as aristolochia faveolate. It turns out to be the host plant of the birdwing and it is found abundantly in the Kiau forests. Homestay owners can grow these vines and be trained to breed the birdwing to increase its number, thus raising the chances of tourists seeing them.

Deforestation remains the biggest threat to the butterfly. Highland forests have been logged for valuable timber, and land cleared for tourism projects such as a golf course and hotels. Dr Sutton warns that the Kinabalu Birdwing “will go extinct if too much forest is cut down” – perhaps long before climate change takes its toll on the butterfly. Environmentalists say Sabah has lost about 22,900 square km, 40 percent, of its rainforest in the past 50 years, representing about a third of Sabah land mass.

For now there’s just hope. State officials say making the Kinabalu Birdwing as Sabah’s state butterfly is expected to create public awareness of the dangers it faces and bring Sabah into focus as an important hub of insect biodiversity. “This will not only capture the hearts of nature enthusiasts but also contribute to our conservation efforts, indirectly ensuring the preservation of its habitat,” says Christina Liew, minister of tourism, culture and environment.

There are no studies to show how climate change has affected the Kinabalu Birdwing. But scientists of the University of York in England have found the first evidence that rising temperatures have caused moths on Mount Kinabalu to shrink in size over a 42-year period. The moths have smaller body and wing size as they move higher up the mountain to escape rising temperatures.

The implication is that the moth population may decrease as the smaller moths will eat less food and lay less eggs. Scientists warn that what has happened to the moths may happen to the birdwing and other insects. Dr Sutton says the birdwing is threatened if the climate gets too hot as it needs cool and wet climate. “We are trying to introduce the Birdwing as an icon representing the potential plight of the montane forest-adapted insects of Borneo.”